By: Deborah Coyne

To download this ebook in .pdf, click here.

Preface

I first published Reform or Revolt: How Canadians Can Take Back Our Democracy, as we were headed into the 2019 federal election. My concern was to identify why, election after election, Canadians who could bring themselves to vote, trudged off to the polls feeling decidedly unenthusiastic about their choices. It was as if we were being shunted to the sidelines of a rigged political game. Election after election, we settle for mediocre leadership cadres focused on short-term power plays that serve their re-election.

Two years later, nothing has changed.

My conclusion then and now is that Canadians are trapped in an autocratic political system—a faux democracy—that increasingly undermines our democratic values of justice, fairness, and equality of opportunity for all. We are trapped in a political system that values loyalty and sycophancy to political party leaders, over a genuine commitment to the people of Canada and strengthening of our shared citizenship and responsibilities for one another.

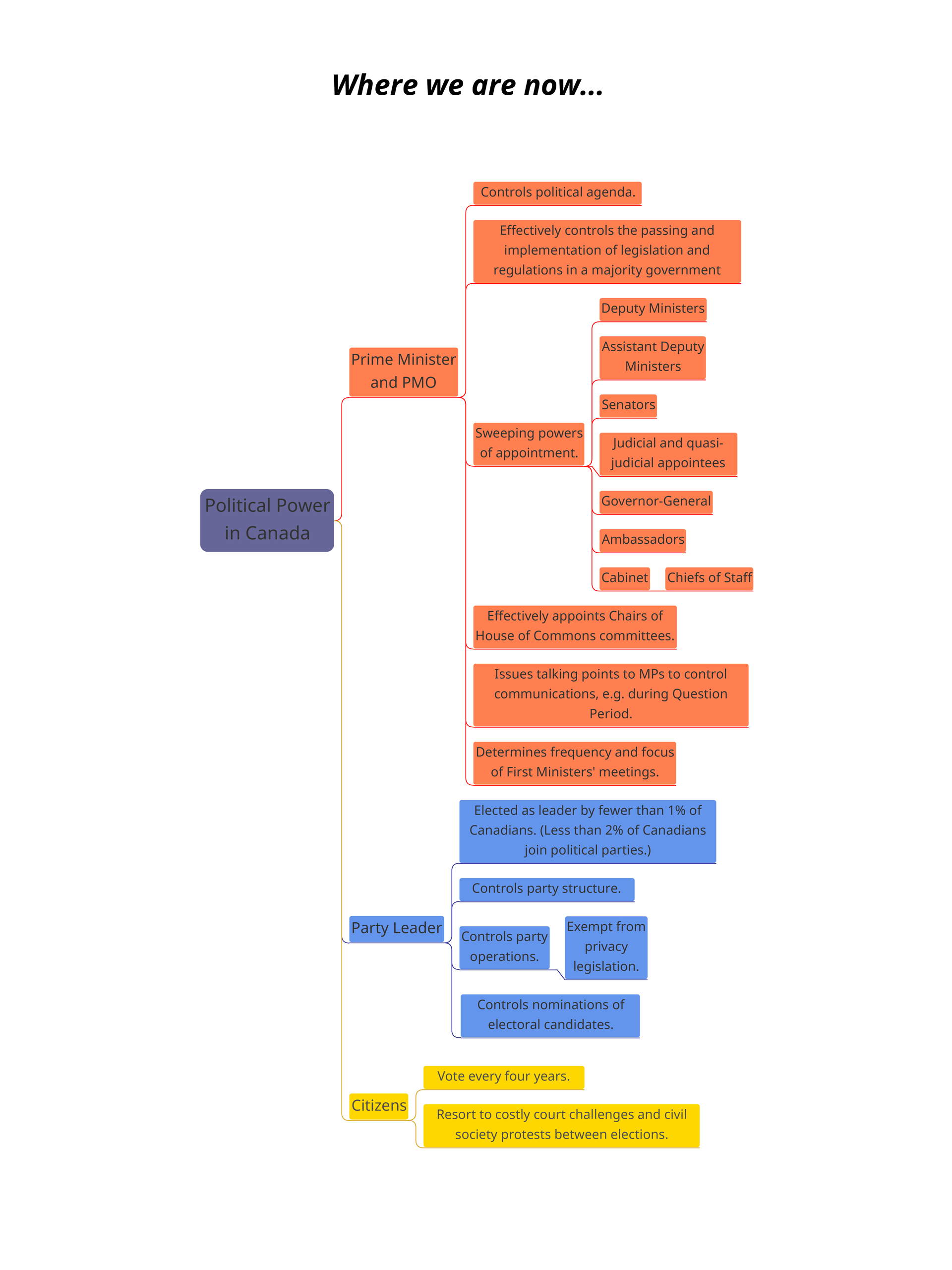

We have democracy in name only. Yes, everyone has the right to vote, and yes, we do not face the open challenge to voting rights and the toxic legacy of Donald Trump that is playing out in the US. But, in Canada, the exercise of political power is controlled by a tight clique surrounding the political party leaders. Democratic institutions and practices are increasingly hijacked by political parties. The federal government is controlled by a Prime Minister’s Office that orchestrates the business of legislating and making judicial and administrative appointments with a view to maintaining and enhancing its partisan power, with minimal accountability. Even serious ethical breaches attract few consequences.

If this autocratic control and lack of accountability continues apace, as it has even through two years of a minority government at the federal level, our democracy is at serious risk. And the democratic decay at the top is compounded by an anachronistic electoral system that produces governments that do not reflect the popular vote, and a Parliament in which MPs are unable to function freely in holding government to account.

The Rise of Canadas’s Faux Democracy

The rise of Canada’s faux democracy represents a dangerous inflection point in our history. We can either start reigning in the faux democrats now, or face more and more unresponsive government, and more and more people turning away from democratic values and practices. Costly court challenges will not be enough. We require direct, coordinated citizen action to bring about concrete, structural changes to the wide range of representative institutions and practices that have been hijacked by faux democrats.

What are the dangers we face?

First, faux democratic governments act in ways that disrespect the constitution and undermine the foundations of our democracy in order to serve political expedience and enlarge executive powers at the expense of our rights and freedoms. In Canada, these include the use of the Charter’s notwithstanding clause and ongoing attempts to amend the constitution without citizen involvement and support. These attempts have required serious citizen mobilizations to prevent them in the past, not always successfully.

Faux democrats consolidate power through perfecting the art of identity politics. Dividing citizens into manageable identity-based groups with separate needs and demands allows faux democrats to target limited initiatives to citizens, appealing to narrow identity-related concerns in order to lock in their support at election time. But this undermines the fundamentals of liberal democracy that depend on recognizing the dignity of all individuals and the legal, civil and moral equality of all people, regardless of identity. Such universal recognition is the precondition to developing the crucial social and economic policies that improve opportunities and bring us all together. And this is what will ultimately enable us to marginalize bigotry and lies, allow reason and compassion to prevail; and achieve real progress in which we correct the mistakes of the past, not just apologize for them.

Second, faux democratic governments avoid undertaking long-term initiatives to address the major challenges we face as Canadians. Such challenges are too often considered high risk politically. And, because they may take more than a four-year term to resolve, deliver no neatly packaged success stories to present at election time. Majority governments – common under our antiquated first-past-the-post electoral system – allow faux democrats to govern using a short-term electoral calculus, in which winning the next election trumps the broader collective interests of Canadians.

As a result, we were tragically unprepared for the pandemic despite clear warnings after SARS in the early 2000s, and are now losing the race to contain accelerating climate change and extreme weather events. Then there is our appalling failure, spanning decades, to take sustained and meaningful action on reconciliation with Indigenous peoples. In the most recent Parliament, serial government ethical transgressions continue unchecked by conveniently inadequate conflict of interest and ethical rules. Sexual misconduct and misogyny appear to be tolerated in the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) even after a blistering report over five years ago. And the much re-cycled, unfulfilled promises for childcare, pharmacare, and so many other beneficial initiatives will soon languish once again in the wake of yet another faux democratic election campaign.

Third, faux democratic governments can gradually and insidiously undermine the rule of law. As citizens become more and more disillusioned with the lack of responsiveness of our governments, disadvantaged groups and individuals feel justified in turning to direct action that disrespects law and regulation. This is compounded by the dysfunction in our federation that has no incentives for constructive collaboration and harmonization across jurisdictions, and instead, encourages governments at all levels to pursue short-term partisan goals and simply resort to blaming other levels for the inevitable policy failures.

Part I: Reigning in faux democrats, and restoring the foundations of constitutional democracy

Despite the patriation of our constitution and the introduction of a Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982, faux democratic leaders continue to challenge the foundational constitutional principle that democratic power, derived from the people, resides with the people. They sometimes succeed. This is because there are fundamental flaws in our constitutional architecture that facilitate the undermining of the constitution and our rights and freedoms.

These flaws date back to 1982. The absence of a referendum mechanism in the constitutional amending formula and the lack of a meaningful constitutional preamble describing modern-day Canada were compounded by the insertion of a notwithstanding clause in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The result has been a constitution which fails to make clear that the Canadian people—not governments—are the foundation of our constitutional democracy.

The flaws are the result of the painful process of accommodating the demands of self-interested premiers in 1982, who unlike the people of Canada, had to be dragged kicking and screaming into a world of guaranteed rights and freedoms. In particular, achieving a Charter of Rights and Freedoms was considered worth the sacrifice of including the notwithstanding clause. But this is no longer the case today, with almost 40 years of experience with the Charter under our belt, and now facing a worsening democratic crisis.

In Chapter 2, I discuss in detail the lessons from the massive citizen mobilization that eventually brought down the Meech and Charlottetown Accords, culminating in the Charlottetown referendum vote in October 1992. Meech and Charlottetown illustrate well the ease with which political leaders tried to use the constitution as an instrument to assist in achieving partisan goals.

A straight line can now be drawn from Brian Mulroney and his fellow federal and provincial leaders in 1987 attempting to appease a Quebec government with the controversial constitutional amendments in the Meech and Charlottetown Accords, through to the current Prime Minister and his fellow federal political leaders in 2021 attempting to appease another Quebec government with equally controversial constitutional amendments in Bill 96.

These constitutional initiatives are all executive-driven with little or no input from citizens. They are designed primarily to troll for votes in Quebec, not for the greater good of Canada and the Canadian people. And these constitutional initiatives all undermine our Charter rights and freedoms and destabilize an already dysfunctional and highly decentralized federation.

In addition, the shamefully uncritical acceptance of the unilateral Quebec amendment to recognize both Quebecers and Quebec as a nation (Bill 96) is matched only by the equally shameful failure of our leaders to condemn in 2019 Quebec’s Bill 21 restricting religious freedom, as well as the reprehensible pre-emptive use of the notwithstanding clause.

So, what can be done to ensure our constitution can endure as a vibrant instrument of the people, by the people, for the people, rather than be weakened by faux democratic politicians intent on expanding their partisan powers?

Proposals are put forward in Chapters 3 for empowering citizens between elections such as through citizen ballot initiatives and consultative referenda.

Chapter 4 describes how social media has changed the rules of political engagement and can, with some guidelines, play a positive role in facilitating citizen involvement and holding governments accountable to the people.

Chapter 5 includes proposals for constitutional reforms to strengthen protections against the arbitrary exercise of power that undermines the rights and freedoms guaranteed equally to all Canadians.

Part II: Reforms to representative institutions and practices

To ensure accountable and responsive government acting in the long-term interest of all Canadians requires methodically implementing a wide range of reforms to strengthen our representative institutions and practices and put an end to debilitating faux democratic forces.

Chapter 6 explains how insular, unrepresentative, and unaccountable political parties are the major culprits in entrenching faux democracy, and in turning politics into an elite sport for the select few. At the very least, reforms are necessary to require more oversight by Elections Canada and the Privacy Commissioner.

Political parties were intended as an institution to make it easier for people to engage in political life, to organize around certain principles, and to make meaningful choices about who should be elected to represent us. However, over time, political parties were taken over by rival cliques, who controlled membership and developed what we now know as the “game of politics.” Ordinary citizens who had little time for this game were increasingly sidelined and persuaded that as long as they exercised their right to vote at election time, the rest could be left to the expert political operatives.

Sadly, the Canadian people have no real influence over the candidates we are presented with at election time. The leaders of the political parties, themselves selected by an unrepresentative segment of the population who have signed up as supporters of a party or leadership candidate, control the nomination of candidates at the riding level. This ensures that the only persons who can be elected are those who support the leader and will submit willingly to party discipline imposed by the leader. It means implementing policies and programs that are designed primarily to ensure the re-election of the leader and the leader’s supporters.

Chapter 7 discusses overdue electoral reform and an end to our antiquated first-past-the-post (FPTP) electoral system which regularly permits the election of majority governments with less than 40 per cent of the vote and the election of a Parliament that does not reflect the popular vote. Most Canadians feel that their preferred party or candidate did not get elected and that they, therefore, have no real influence in parliament.

Chapter 8 details many reforms to parliamentary institutions and practices which are essential to holding governments accountable to both Parliament and the people and to greater oversight between elections—such as eliminating omnibus bills and implementing whistleblower legislation, greater access to information, ethics guidelines, and lobbying regulations. Successive governments have failed to implement any restraints to their autocratic powers. The time is now overdue for elected representatives to work across party lines and build new governing coalitions outside the parties to stop the democratic decay.

Despite being reduced to minority government status in the 2019 election, the pandemic allowed the Liberals to govern as if they had a majority and to continue to treat Parliament with disrespect. Huge omnibus bills that prevent adequate scrutiny and accountability have become commonplace. For example, Bill C-30, the 2021 Budget Implementation Bill, was over 700 pages in length. In August 2020, the government simply prorogued Parliament to avoid accountability for the WE Charity scandal. In June 2021, in an unprecedented attack on the authority of Parliament, the Liberal government went to court to challenge the right of the House of Commons to demand documents from the government.

There has been a particularly disturbing lack of transparency and useful information about the government’s pandemic response. For example, why did the federal government fail to fulfill its longstanding responsibility to maintain adequate supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE)? The absence of mechanisms for ensuring accountability and transparency on the part of the federal government must be corrected urgently.

Now the government is preparing to trigger an unnecessary election simply because it would like to resume its autocratic governance, unfettered by even the minimal inconveniences caused by the minority government.

Despite the fact that in accordance with the Canada Elections Act a federal election should next be held on October 16, 2023, the government claims that it cannot get its legislation passed and needs a new mandate now. Yet in fact, the government has been able to pass all the legislation that it deemed necessary. So, the push for an early election is simply code for saying “we want a majority government.”

The government and opposition parties will rely on the short attention span of the electorate. On election day, they hope we will remember only carefully-crafted micro messaging about narrow issues carefully curated by politicians. This will persuade us to vote for representatives of particular political parties. The focus will be on personalities and stunts, vague statements, and word salads, and of course fear. The name of the game is to polarize opinion around wedge issues wherever possible, so that the voter is convinced that one political party or another will do something terrible that must be avoided at all costs.

The danger of deliberately polarizing debate around a manufactured fear of the opposition is that it deflects our attention from a campaign devoid of any substantive policies and proposals to address the inequities and hardships faced by so many disadvantaged and alienated citizens. So, the next government is elected without any mandate for which they can be held accountable. And the many disadvantaged and alienated citizens then give up on government and are open to listening to, and following, the angry voices of extremist elements whether on the left or right.

Chapter 9 addresses the specific subject of raising adequate revenues and undertaking comprehensive tax reform. This topic merits its own chapter since, without proper financing, we can never deliver effectively on crucial initiatives to address the needs of so many disadvantaged and alienated Canadians, and guarantee access to justice, equal opportunities and the essentials of our shared citizenship. For example, if we are serious about finally moving beyond empty rhetoric, why not dedicate an immediate 1 or 2 percent of GST to Indigenous peoples to solve clearly defined issues?

Part III: Fixing federal dysfunction

The inadequate capacities of our federal and provincial governments for long-term public policy planning and constructive collaboration across jurisdictional and other boundaries has sadly persisted for decades. The pandemic response by governments revealed this clearly. Why, for example, were we so slow to change the guidance on masking and travel bans? Why did we so easily forget the lessons of the 2002 to 2004 SARS epidemic and abandon the pandemic early-warning system? Why were we unable to maintain adequate vaccine manufacturing in Canada?

Should we now revisit the Emergencies Act and the possibility of a coalition government handling the next emergency more effectively? Is there not a compelling national interest to have common pandemic and emergency rules across the country? How do we better coordinate the crucial production and distribution of vaccines? Should we have clear national rules regarding the requirements of Canadians to be vaccinated, whether for travel, school, or other reasons?

More generally, Covid-19 has disproportionately impacted disadvantaged Canadians relating to both health and income. These are the millions of Canadians unable to work, or study, from home, and who are least able to withstand a sudden loss of income that would affect paying rent and other essential aspects of daily life. These are our fellow citizens who suffer most from the lack of high-quality childcare and health care, sick pay, public infrastructure, and access to quality education.

The inability to demand substantive debate and to hold our leaders accountable across jurisdictions in our federation is one of the most serious threats to the survival of a vibrant democracy and our basic democratic values today.

Action to repair our dysfunctional federal system and ensure effective and efficient collaboration across all levels of government is crucial if we are serious about national initiatives that could benefit all Canadians.

Chapter 10 discusses how to modernize our federation and reform intergovernmental institutions and practices to achieve better results for all Canadians and strengthen the foundations of our democracy and representative institutions and practices.

One suggestion to update our federal structure, among other things, is to establish a Council of Canadian Governments. An institution like this, providing a tradition of coordination across provincial, municipal, Indigenous and federal governments, would have been helpful in this pandemic. Australia had a Council of Australian Governments for almost 30 years, from 1992 to 2020. This may explain, in part, why Australia was better prepared than Canada to coordinate action across state governments and get a grip on the spread of Covid-19 during the early weeks of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Chapter 11 considers five critical policy areas that need serious and sustained intergovernmental harmonization, and that would greatly benefit all Canadians. These are: climate change mitigation; improved income security; eliminating interprovincial barriers to trade, employment and carrying on business; coordinated training and support for workers; and improved access to healthcare.

Conclusion

Despite the continuous and tiresome refrain that politics is a game and that we cannot expect significant change, I refuse to give up hope for something better. In this book, I describe the personal experiences that have informed my political views and my proposals for change. Even though I have left active politics, I am deeply concerned about the serious democratic decay in our representative institutions and practices and hope my accounts and observations may contribute to informed debate about the way forward to a true democracy.

I conclude with the hope that citizens will be persuaded that restoring and strengthening our democracy is a goal worth fighting for, issue by issue, for as long as it takes. Citizen engagement can play out in many different forums and many different ways, during and between elections. What must unify us is our shared determination to work outside political parties, in non-partisan action groups focused on our serious collective challenges, to take control of the political agenda, bring about the crucial reforms to our representative institutions and practices, and demand much more from our elected representatives.

Enjoy the read. Don’t be a bystander on the sidelines of history. Speak up and take action to do something to overcome Canada’s faux democracy and to build a more truly democratic nation.

Deborah Coyne

July 2021

Introduction

The Rise of Faux Democracy

“None of the above.” This is the all-too-common response of Canadians when asked who they support in politics today. “Uninspiring”, “ineffective’, “out-of-touch”, and “self-absorbed” are the kind of words we use to describe our representatives. Why are we settling for such mediocrity?

This book stems from an unusual opportunity I had to review my past political activities and organize almost 30 years of writings and thoughts. Crucially, ‘political’ in my case implies not only “relating to the government and public affairs of a country” but also “of or relating to citizens.” Although I spent decades immersing myself in the minutiae of government at all levels, our constitution and our laws, my most constructive political experiences involved popular, citizen mobilization outside of the political establishment. I remain fascinated by how we can use representative institutions and practices to improve our collective future, and shape a society where preserving the dignity of our fellow citizens—especially the disenfranchised—preserves the dignity of us all.

What became regrettably evident in my review was Canadian democratic institutions have continuously let citizens down. We have allowed the established political parties to take control of the democratic process away from citizens and run it like an elite sport—a faux democracy. Year after year, the political class in power carefully calibrates (and in the process, trivializes) the conduct of governance to support its re-election, while Canadians express endless frustration over unaccountable, unresponsive government. Election after election, citizens trudge off to vote, less and less enthusiastically (if at all), confined to the sidelines of a rigged political game.

It’s my hope that my book will provide a roadmap to fundamentally reforming our hijacked political structures—to putting engaged citizens back at the centre of our democratic system; and sidelining the political parties that are polarizing politics and constraining our civic space.

Here is something I wrote in 2013, when I was still actively engaged in federal politics in an effort to improve our democracy:

“Like many Canadians, I have lost confidence in the fundamentals of our democratic system, along with the idea of an honest and efficient government. I’m frustrated by endless reports of wasted money and ineffective programs. I resent years of leaders creating short-term opportunities for consumption instead of long-term opportunities for education and employment, leaving us spectacularly unprepared for an age of restraint and environmental devastation. Sadly, especially for many young people, it’s much easier to give up on politics altogether and settle for mediocrity and low expectations.”

I believed we could do politics differently, that we could overcome pervasive spin, manipulation, and obsession with partisan political agendas. Yet today, we find ourselves further than ever from achieving this goal, with a political establishment incapable of enacting the change we so vitally need.

This book is about how citizens must take back control from autocratic, self-absorbed political parties and end our faux democracy. We must build up Canada’s democratic institutions to support a sustainable, just and prosperous society capable of surmounting turbulent times ahead.

Citizen discontent with government and the established political parties is rising, although the political elite’s evident distrust of citizens is even greater. The establishment spends most of their energy managing and sidelining citizen engagement between elections. Hence, the ruling party’s obsession with controlling decision-making and messaging, manipulating one or another voting group, and creating wedge issues to needle the opposition––all with a view to successful re-election.

But the Samara Centre for Democracy’s 2019 report called “Don’t Blame The People: The Rise of Elite-led Populism in Canada,” perceptively notes that “democracy is all about people and a healthy democracy requires much more than an election every four years. A healthy democracy requires regular engagement from a wide swath of citizens, or it does, indeed, become a plaything of the elite.”

Today, too many Canadians—I call us “sidelined citizens”—neither buy into worn-out political rhetoric about middle-class aspirations, nor see any measurable value in tax cuts or tax benefits for children or workers. Nor do we see any government initiatives that significantly assuage our anxiety about our precarious living conditions, and our social economy’s ominous future. Instead, we see inequality increasing every day and stagnant or declining economic opportunity, with any rise in incomes still significantly skewed toward the highest earners. With every increase in secure salaries, gold-plated benefits and expense accounts for politicians, and each report of out-of-control pay for private sector CEOs and directors, citizens see more evidence that our democracy is far from a leveling system. As things stand, non-elites have no real say in building a society that assures equal access to opportunities.

If citizen cynicism and frustration reach a tipping point, if inequality continues to accelerate, if prosperity and progress always seem to happen to other people, if enough Canadians continue living precariously close to the edge, under- and unemployed, conditions will soon be ripe for a reaction that could destroy, rather than strengthen, our democracy.

One thing is for certain: we can no longer take the lazy route and expect to find the perfect leader—the “Enlightened One”—who will somehow make everything right. The Liberal government, like Harper’s before it, has become too comfortable with power and privilege. Loyalty to the leader is valued above all else; when loyalty is challenged, as in the 2018–19 Jody Wilson-Raybould case, the individual who resists is punished. Politics is viewed as a leader-centred sport, secretive and controlled, focused on the next election instead of Canada’s long-term interests. Long-time political pundit Susan Delacourt describes the Trudeau government as the most cliquish she has experienced.

Small wonder there’s a general sense of disappointment and cynicism towards the Liberal government. They come off as good at rhetoric and grand gestures, endlessly repeating their commitment to helping the (aspiring) middle class; but insincere—powerless or unwilling to take necessary, innovative, and transformative steps to genuinely help struggling Canadians. And when Liberals resort to vilifying the opposition in an effort to obscure their inaction, citizens are not fooled.

Most Canadians, especially millennials and generation Z, understand the need for government to underpin a strong social economy. In our intensely networked 21st-century world, we have an overload of information about the challenges we face, from unemployment and poverty to climate change, financial crises to pandemics, cyber-crime to terrorism. But we are frustrated. We lack governments and politicians capable of undertaking crucial, long-term collective action.

Why?

Two negative forces are at play, each compounding the harmful impact caused by the other.

First, our governance structure is far too top-down. Politicians at all levels are much too focused on the election cycle and short-term re-election plans. Power brokers within closed party hierarchies set policy agendas, while citizens’ political energy at the grass-roots level—even within large-scale movements such as Occupy Wall Street or Idle No More, Me Too, and Black Lives Matter—struggles to be translated into effective political power and change.

Second, our federal system discourages collaboration and harmonization across jurisdictions. Different levels of government often act at cross purposes, and blame the other levels when something goes wrong. Without adequate transparency, citizens can never accurately assess accountability.

So how do we change this?

We need an urgent rebalancing of executive and citizen power, so that political power is no longer concentrated in party leaders, and government can genuinely respond to citizens’ concerns and carry out an innovative, ambitious agenda through greater collaboration and compromise. We must reform our democratic institutions and practices, and create new norms based on cooperation, finding common civic goals, and shared respect. As citizens, we have to focus our energy, skills and grass-roots experience on mobilizing outside of political parties, and demand much more of our individual candidates.

We also need to eliminate the dysfunction of our federal system. This means co-ordinating governance so that all levels of government work together—despite varied election cycles—to create national frameworks that support coherent actions and regulations in the many areas that cut across jurisdictions and deeply affect our daily lives.

Our entire system needs overhauling, from our representative institutions to intergovernmental relations. We desperately need to cultivate an environment that encourages consensus among all of our elected representatives, and across all levels of government. We want elections to be about mobilizing Canadians around inspiring, long-term plans of action, rather than familiar, all-too-fleeting personalities.

In this book, I’ll discuss the steps required to end Canada’s faux democracy and build a new governing coalition outside the established parties. This means taking back citizen control from autocratic, self-absorbed political parties, extensive reforms to representative institutions and practices to ensure more transparent, accountable and responsive government, changes to our electoral system and encouraging more independence among our elected representatives. I suggest that in seeking ways of strengthening our democracy, it is important to examine and understand the stories of those who have failed to gain influence in the current structures, rather than the very few who have succeeded in playing the rigged game well. It is equally vital to learn from past experiences of popular mobilization for change––experiences all too often omitted from our history books.

Canadians must get off the sidelines and take back the initiative to define Canada’s future from self-serving political machines. During elections, this means choosing to support the most thoughtful, principled candidates—regardless of any political affiliation. Far better to elect, riding by riding, a Parliament of trustworthy, independent-minded representatives, than to seek the perfect leader in whom all power is vested. To do this, voters—either individually or through civil society groups—must attend all-candidate meetings, speak to candidates at the door, and require firm commitments to implementing specific democratic reforms. For instance, in exchange for our support, we should demand that candidates vote independently in their legislatures, replace the first-past-the-post electoral system, and impose legal limits on the executive power of the prime minister, as well as leaders at all levels of government.

Either we rise up and insist on serious reform, or our politics will continue to be dominated by privileged elites who consider it a mere game to be fought and won, with citizens there to be manipulated, not served. Complacency is dangerous. It’s time to take action.

Chapter 1

The System is broken: Democracy in peril

You are sitting on the roadside in a broken-down transit bus or mired in endless traffic along one of our nation’s highways. You are employed but your salary is never enough, or you are unemployed and looking, still looking. Your thoughts turn to you and your family’s state of affairs. You were hoping for a tiny, 1 percent increase in the minimum wage, but a new provincial government has abruptly revoked it.

What about that national childcare program? That would really make a difference, but successive federal governments have talked about it for more than 25 years and nothing has materialized.

How about income support to survive the evermore precarious living conditions associated with having to work multiple jobs in the ‘gig economy’? What about enforceable employment standards to protect against the crazy and unpredictable shifts imposed on you? Or comparable and accessible training across all provinces that would enable you to take up decent work anywhere in Canada?

Maybe, you think, if your vote had some impact, things would improve. But try as you might to select the best local candidate, the best leader and the best political party, nothing seems to change. A new government may start by fulfilling some promises, but within months the impact on citizens—you—does not match the rhetoric. What follows is polarizing debate and intergovernmental squabbling—federal, provincial, municipal, Indigenous—which makes progress on important initiatives glacially slow, or even cancels them, from carbon pricing to the minimum wage and a basic income experiment.

Eventually, a few long-ignored promises might re-appear, but only a few months before an election.

Meanwhile, you’re a parent of a child with a disability or a family living on the edge without affordable housing, and suddenly you find yourself faced with a government’s decision to reverse critical funding you had been relying on. You have neither the time nor energy to protest; you simply have to wait another four years until the next election for your vote to possibly make an impact. But by then you don’t know where your life will be—your children never stop growing and getting older, and only a steady job with a living wage and access to effective social services will provide you with the dignity and security to survive.

Our reaction, as citizens, is to conclude that political action is hopeless and retreat to the sidelines. We give up, struggle along with our lives, and increasingly rely on overstretched volunteer services, charities, or, where possible, our families, to help out. All too often we don’t bother to vote. It seems to make no difference.

We most certainly don’t get involved in political parties to bring about change. We’re now convinced that political parties claiming to have popular support are a sham: weak on principles and lacking long-term vision and goals. Leaders and their close advisors manipulate messaging and massage policies so they can claim that voters are aligned with their objectives. Then once they are elected, especially with a majority government, every initiative must pass the ‘can I get re-elected on this’ test, rather than aligning it with the public interest. This leads to mediocre leadership designed primarily for the benefit of the governing party, not the citizens of Canada.

Understandably, we are frustrated and cynical, alienated from the very individuals and organizations that are supposed to represent us and enable us to act collectively for the good of all. They appear blatantly out-of-touch and unresponsive, unable to manage the complex challenges facing every modern democracy.

If any of this resonates with you, then you are a member of a large and growing group of what I call “sidelined citizens”—those who have been let down by our basic democratic structures. When citizens are sidelined, political dialogue is polarized, driving out principles and long-term vision.Despite Canada’s reputation for moderation, tolerance, and inclusion, we, too, are vulnerable to pernicious, divisive forces.

I come at this with over a decade’s personal experience with the traditional party system, which I discuss in Chapter 6. Between 2005 and 2014, I was involved in three nomination contests to be a candidate for the Liberal Party of Canada. I also ran as a Liberal candidate in the 2006 general election. Along the way, I received advice from party insiders that I just had to play the political “game” nicely, wait my turn, accept that it’s all about luck and timing in so-called “winnable” ridings—code for doing all you can to get the leader’s personal support for your candidacy. In 2012–13, I joined the race for the leadership of the Liberal Party, a further education in how the system works.

In 2015, I transitioned out of the Liberal party in favour of a very refreshing stint as policy advisor to Elizabeth May and running as a Green Party candidate in the 2015 General Election. The Green Party was a very open party, with a generally thoughtful, diverse membership and an able and articulate leader, but without debilitating control from the leader’s office.

I have since left partisan politics, and I see the political party system as increasingly backstopping our faux democracy, and an obstacle to much-needed and overdue change.

Most Canadians today are thoroughly disillusioned with our established political parties. Our leaders rule by distraction and diversion, and appeal to the lowest common denominator. They seem content to spout empty rhetoric and rely on appearance over action. They pander to their bases and seek to vilify the others. Meanwhile our democracy is increasingly ill-equipped to confront the enormous challenges that lie ahead. The COVID-19 pandemic is only the latest example to add to climate change, the effects of automation and technological disruption, our need for increased immigration while managing huge movements of people fleeing poverty, war, and crime.

As the gap between political elites and ordinary citizens has widened over the past couple of decades, it has stoked populist movements that give voice to widespread frustration outside of the political establishment. Broad-based, popular engagement with civil concerns is invaluable—an indication of the need for serious change, and of citizens’ motivation to participate in transforming the status quo. But in the absence of a vibrant, inclusive civic space and strong democratic infrastructure, it can be co-opted by otherwise marginal far-right extremists and neo-Nazis, who use social media’s echo-chamber effect of information and misinformation, a potent weapon that makes it hard for many to distinguish between what is true and false.

At times like this, our democratic institutions prove fragile, and we see wild swings from one extreme policy agenda to another. In Ontario, for example, the provincial government took a step forward in introducing a basic annual income pilot project and increasing the minimum wage, only to see the next government eliminate the annual income experiment and cancel the minimum wage increase. Canada’s political debate could all too easily degenerate into the corrosive polarization that overwhelms America.

To end this cycle of cynicism and polarization, and ensure our democratic institutions are strong and responsive to the needs of citizens, all of us need to get involved. This isn’t the time for passivity. It is the time for mobilizing to save our democracy and maintaining constant vigilance.

Citizen action must call for long-overdue reforms to our representative institutions and practices, re-establish responsible government, and repair what so many disillusioned voters see as a broken social contract undermining our democracy. Unfortunately, the kind of reforms we need—that enable both the clear articulation of specific long-term goals reflecting a broad consensus, and the establishment of a practical action plan for implementation, and funding—are impossible in current circumstances. So long as the established political parties have a monopoly over the levers of power, they will refuse to take any action that undermines the ruling party leader’s effective control over the legislative process.

In the 2015 general election, the Liberal Party, the New Democratic Party, and the Green Party all promised a whole raft of accountability, open government, and electoral reforms affecting the operation of Parliament and designed to diminish the power of the Prime Minister’s Office. Among other things, these would have resulted in freedom for MPs to act outside their partisan bubbles. The result is less polarization and more effective government action.

But as we have seen, once the Liberal Party of Canada elected a majority of MPs, these reforms were ignored, sacrificed on the altar of getting re-elected. The government settled for a short-term agenda of half measures that can easily be erased by the next government. With notable exceptions, like Liberal cabinet ministers Jody Wilson-Raybould and Jane Philpott who were at the centre of 2019’s most explosive political controversy, the majority of MPs are convinced by the leader that politics is dependent on their absolute support of Party through its leader, even when this undermines the national interest of the Canadian people. So, instead of the promised new way of doing politics, the federal Liberals have treated us to widespread sycophancy, together with the same recitation of mindless, PMO-drafted talking points that characterized the Stephen Harper era.

* * *

Nothing better symbolizes my thesis than the 2019 SNC-Lavalin affair, which featured Jody Wilson-Raybould, a prominent Indigenous politician, who held two high-profile positions in the Liberal cabinet—Minister of Justice and Attorney General—from 2015 to January 2019. In her role as Attorney General, she had decided not to overrule a decision by the Director of Public Prosecutions to pursue charges of corruption and fraud against the Quebec engineering multinational SNC-Lavalin. Wilson-Raybould later reported that she was subjected to repeated overtures by cabinet colleagues and officials from the PMO trying to convince her to change her mind. After Treasury Board President Scott Brison resigned in January 2019, it provided the Prime Minister with an opportunity he couldn’t resist. In a cabinet shuffle on January 14, he reportedly moved Wilson-Raybould first to Indigenous Services and then, after she refused the post which would require her to administer the Indian Act, to Veterans Affairs—widely seen as a demotion. The Prime Minister also replaced Brison at the Treasury Board with former Indigenous Affairs Minister Jane Philpott, a move seen as a promotion but in fact was a convenient way to neutralize both Philpott and Wilson-Raybould, who were often allied in cabinet against the PMO’s preferred direction in Indigenous matters.

On February 7, The Globe and Mail published a story, citing unnamed sources, reporting that Wilson-Raybould’s “lack of cooperation” as Justice Minister and Attorney General was the main reason she was removed from the portfolio. Five days later Wilson-Raybould resigned from her cabinet post and at the end of the month appeared before the Commons justice committee and stated that she felt intense political pressure and veiled threats relating to the SNC-Lavalin file. A few days later, Philpott resigned from her Treasury Board post saying, “Sadly, I have lost confidence in how the government has dealt with this matter and in how it responded to the issues raised… I must abide by my core values, my ethical responsibilities and constitutional obligations….”

It was a dramatic moment, but all the more so for those who recalled the day Justin Trudeau was sworn in as prime minister, standing in front of his cabinet made up of 15 women and 15 men. When he was asked why a gender balance mattered, he held up his hands and said, “Because it’s 2015.” Three years later, the self-proclaimed feminist appeared to have been too clever by half.

With the prime minister’s minions in overdrive trying to protect him and limit his direct involvement in the controversy, Wilson-Raybould produced another bombshell. In December 2018, when various government representatives were pressuring her, she voice-recorded a call from then-clerk of the Privy Council Michael Wernick that dashed all denials that the Prime Minister had been aggressively involved in protecting the interests of SNC Lavalin. In part, Wernick said: “I think he is gonna find a way to get it done one way or another… he is in that kinda mood and I wanted you to be aware of that… he is in a pretty firm frame of mind about this so… I am a bit worried… It is not a good idea for the prime minister and his Attorney General to be at loggerheads.”

My take on all this is that Jody Wilson-Raybould is among our rare principled politicians. She correctly identified and resisted attempts by the Prime Minister and his advisors to pressure the Attorney General to undermine prosecutorial independence. Jane Philpott, likewise, stood up “for principle, truth, and justice,” resigning to protest the cabinet’s decision to support the government’s handling of the SNC-Lavalin affair. Finally, on April 2, 2019, the Prime Minister ejected both women from the Liberal caucus—a decision that was his alone, because the Liberal caucus had failed to adopt for itself the power to decide its own membership. In fact, the caucus had failed to even hold a vote on whether to adopt that power, despite being required to do so in the Parliament of Canada Act.

Wilson-Raybould and Philpott were both cabinet ministers when they stared down the Prime Minister and his acolytes. Pity the poor backbencher. Author and political scientist Alex Marland, the author of a book about how party discipline has intensified in Canada, Whipped, Party Discipline in Canada (2020), has written “Backbenchers are unfairly derided by pundits as trained seals who mindlessly follow their masters’ orders. In reality, they are interesting people who get involved in party politics hoping to make a difference. But too often independent thinking does give way to a team mentality. The transformation begins the moment they sign a “values contract” when they want to be nominated as party candidates. The contract is signed during the candidate vetting process to screen out people who might attract negative attention during a campaign and those unwilling to commit to the party’s core values, such as the principles articulated in the party constitution. The team ethos is reinforced through a daily barrage of digital messages, including hashtags that emphasize the team leader (such as #TeamTrudeau).”

Two camps have emerged in the political sphere:

- The politics as usual/politics as a game camp sees political parties as the personal instrument of the leader for the purpose of winning the next election and staying in power.

- The principled citizen camp refuses to accept that politics is a game and believes in a vibrant citizen-powered democracy. Its members are those who believe we can do better and do not have to settle for mediocrity.

The politics as usual gang set out to undermine the public’s positive perception of both Jody Wilson-Raybould and Jane Philpott as principled heroes. They made a great effort to portray both women as self-interested politicians out only for their own personal glorification. The as usual gang, best symbolized by the team within the PMO, are acolytes and yes-men who argue that politics can only effectively function as a rigorous team sport with fealty to the all-powerful leader. Indeed, Democratic Institutions Minister Karina Gould suggested on CTV that the expulsion of the two women, and preserving caucus unity, was more important than addressing the constitutional breach of judicial independence that is at the core of the controversy. Astute Maclean’s columnist Paul Wells, called this phony but surely it is well-beyond phony. “And since the lot of them never stop calling themselves #TeamTrudeau on Twitter,” Wells wrote, “I guess we can, without fear of contradiction, say the Prime Minister of Canada has been the phony-in-chief.”

Despite initial enthrallment with his celebrity status, good looks, and promise of “sunny ways,” the Liberal leader has demonstrated all too clearly the superficial, self-interested side of Liberal party culture: the arrogance and the suffocatingly centralized party leadership that rules in a bubble.

Citizens are increasingly recognizing this and seeking alternatives. We’re prepared to pass harsh judgment on the faulty moral compass that guides the Liberal government and demand more than carefully-crafted spin from our elected representatives. While we may have concerns, we won’t be scared into voting Liberal because the alternatives are said to be worse.

It is important to understand that this crisis of frustration with government is not without precedent. The popular movement that flourished in opposition to the Meech Lake Accord of the late ‘80s and the Charlottetown Accord of the early ‘90s [more on this in Chapter 2] demonstrated how diverse groups of “critical, engaged and involved citizens”—which the Samara Centre for Democracy considers always good for democracy—can come together to protect and promote the rights and freedoms of all Canadians. According to Samara, constructive, broad-based citizen action is vital if we are to find solutions to the “very real problems [in our democracy today] including centralized control, degraded legislatures, unhealthy political parties and low voter turnout.”

* * *

Just before the 2019 election, I was chatting with a customer service representative at our local post office when she asked me in dismay why the Ontario government cancelled the further increase of the minimum wage in Ontario to $15.00. She couldn’t understand why the new government was so mean, and how something announced by a previous government could be so easily overturned. Among other things, I said that the policy reversal could have been averted if a majority government had not been elected. I explained how a minority government would have provided serious checks on the exercise of power, and likely could have prevented the change.

Excited, she then asked how she could vote for a minority government at the next election. Which led to a further discussion about how a minority government could not be engineered under our first-past-the-post system. We could only try to elect candidates committed to electoral reform. Some form of proportional representation would more accurately reflect the will of citizens and pave the way for coalition governments, which would in turn encourage greater compromise and collaboration, such that new governments would be unable to polarize a sensible policy like raising the minimum wage.

The 2019 federal election encouragingly resulted in a minority Parliament. But unfortunately, the subsequent focus on the pandemic and the reeling economy meant no progress could be made by any opposition parties to insist on reforms to increase accountability and scrutiny of the Liberal government. Indeed, within weeks of the election, the Liberal government abolished the Democratic Institutions portfolio.

And while Jody Wilson-Raybould succeeded in her bid to be re-elected this time as an independent MP, she announced that she will not seek re-election in 2021. According to Wilson-Raybould, “federal politics… is increasingly a disgraceful triumph of harmful partisanship over substantive action.”

Going forward into the next election, we all must exercise our right to vote, especially the over 30 percent who consistently fail to cast their ballots. One person, one vote, is (supposedly) the bedrock of democracies and only by voting can we expect to see positive change. Yet at the same time, we require serious electoral reforms to make our votes count, and to get this, we still have to use the deeply flawed first-past-the-post (FPTP) voting system at least one more time. And, unfortunately, FPTP too often results in flukes, as in 2015, when we got a surprise majority government with the support of only a minority of the population who turned out to vote.

In part, votes had shifted to the Liberals in 2015 because the Liberal leader had a clearly-voiced commitment to pursue electoral reform. But after a Special Committee on Electoral Reform met for most of 2016 and produced a report in December recommending electoral reform and a consultative referendum, the Liberal leader abruptly abandoned the campaign promise. With the media repeating the obvious, but dangerous, conclusion—that Canadians can no longer believe any election promises, an invitation to further cynicism and voter disengagement—this episode proved beyond a doubt that Canada suffers from an autocratic political system in which a prime minister has more executive power than the President of the United States.

The time is overdue to elect a government able and willing to implement transformative reforms to our democratic institutions and practices, including electoral reform. To this end, citizens need to work outside established political parties. We need to devise ways to wrest control from the parties at all stages of the political process, from the selection of candidates to the legislative process. Only by electing more independent and principled MPs, who are encouraged to collaborate across partisan divides, can we take back our democracy and defeat the forces that for too long have treated politics as their private sport and enforced the rules for their own benefit.

One day, a person associated with a thoughtful non-profit, non-partisan organization dedicated to “increasing civic engagement and a more positive public life,” thanked me for my service to Canada over the years. She asked me what I thought I had been able to contribute to public policy or public life during those years of active involvement in politics. Without bitterness, but with some regret, I replied, “nothing.”

I spent most of my adult life refining my thinking about Canada—its values and institutions—and how we can ensure good governance and productive citizenship. But while those goals may have resonated with many fine people along the way, I can honestly conclude that my partisan activity had no meaningful impact whatsoever.

Still, there was one time in my political life I can truly say was a rewarding and effective experience: my involvement in the constitutional debates over the Meech Lake and Charlottetown Accords, from 1987 to 1992. Citizens took matters into their hands and battled around the rigid, insular political elites that were steering the country in the wrong direction. The debates were full of principle and a sense of purpose, providing valuable insights into the hopes and dreams of Canadians across the country. This experience forms the bedrock of much of my thinking on creating political change today.

PART I

REIGNING IN FAUX DEMOCRATS

AND RESTORING THE FOUNDATIONS OF CONSTITUTIONAL DEMOCRACY

Chapter 2 Why Meech and Charlottetown matter:

Lessons in citizen mobilization

Chapter 3 Citizen initiatives and referenda:

Stepping up.

Chapter 4 Changing the rules:

Political engagement and social media today

Chapter 5 Constitutional reforms to strengthen protections

against the arbitrary exercise of power.

Chapter 2

Why Meech and Charlottetown matter today: Lessons in citizen mobilization

How does the Charlottetown referendum, and the five years of debate that preceded it, relate to today? The 1992 referendum saw most of Canada’s population vote against an agreement supported by the political establishment, including every official party. It was a powerful grass-roots message to Canada’s “elite political class” and certainly a preview of how things would develop in this country over the course of subsequent decades. Citizens coordinated a widespread, organized revolt against the lack of transparency and accountability that still plagues political conduct in Canada, both within governments and between different levels of government.

All in all, it was arguably among the two or three most successful citizen mobilizations in Canadian history. Still, according to many in our political, academic and media establishments, it might as well be written out of our history books. This misrepresentation must be changed.

With the 30th anniversary of the Charlottetown Referendum on the horizon, the time is overdue to review the experience and how consultative referenda could play a role in strengthening our increasingly fragile democracies.

This is all the more important because the shameful unanimous acceptance by all our federal leaders of Quebec’s Bill 96 in May 2021 indicates that our faux democrats have learned no lessons from Meech and Charlottetown, and another citizen mobilization may be required in the near future. To have so quickly and thoughtlessly accepted the Quebec government’s brash attempt to unilaterally amend the Canadian constitution to bolster the province’s constitutional status as a nation, together with its pre-emptive use of the notwithstanding clause, should shock all Canadians.

***

More than 30 years ago, Canada faced a constitutional crisis that was resolved by citizen engagement, organised in exactly the kind of movement we need to see today.

It started in 1987 with the Meech Lake Accord, when then-prime minister Brian Mulroney introduced controversial amendments to Canada’s Constitution. The amendments were negotiated with all the premiers to respond to Quebec’s five demands for constitutional change put forward because the Quebec government claimed, incorrectly, that Quebec was excluded from the Canadian constitution. Despite Quebec initially demanding the recognition of Quebec’s distinctiveness in the constitutional preamble as one of its five core demands, what eventually emerged in the Meech Lake Accord was a distinct society clause that undermined the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and other provisions that gravely weakened an already excessively decentralized federation. Meech was presented to Canadians as a take-it-or-leave-it proposition.

Here, we must pause to remember that Quebec was not in fact excluded from the Constitution of 1982. The Constitution of 1982 is the fundamental law of the land throughout Canada, including Quebec, notwithstanding then-Premier René Lévesque’s refusal to sign the final document. Seventy-two of seventy-five Quebec MPs in Parliament voted in favour of the Act, and Quebecers have never since hesitated to rely on the Constitution and its Charter of Rights and Freedoms, in the courts and beyond. If not legally necessary, it nonetheless remains politically desirable that the National Assembly of Quebec formally endorse the 1982 constitutional changes.

In April 1987, I was a young law professor at the University of Toronto reading through the proposed changes to the Constitution. I couldn’t believe how eleven men could have the audacity to sit in camera and then present to the people of Canada changes that would result in a substantial devolution of powers to the provinces, and a substantial reduction in the impact and powers of the federal government. Essentially, Brian Mulroney had conceded each of Quebec’s demands for more powers and, wherever possible, extended these concessions to all the provinces to ensure their support, undermining the Charter in the process. At the very least, there was something wrong with a process that could alter the fundamental law of the land—our basic individual rights and freedoms and basic framework for our representative institutions and practices—without serious consultation and direct input from the people of Canada.

Unfortunately, the flawed constitutional amending formula adopted as part of the historic patriation process in 1982, and the failure to amend the preamble of the constitution to include an inspiring ‘we the people’ provision, leaving only a dry outdated reference to “supremacy of God and the rule of law,” made the first ministers’ controversial action possible in 1987.

The final 1982 amending formula expressly rejected the initial proposal for a referendum mechanism to ensure popular assent for constitutional change that Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and sovereigntist premier René Lévesque of Quebec both supported. But in the final compromise with the recalcitrant provinces outside Quebec who opposed the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the federal government reluctantly agreed not only to an amending formula that requires only legislative votes in the federal and provincial legislatures, but also to the controversial notwithstanding clause, which allows governments to override certain rights and freedoms from time to time. The determination of nine provinces to hold out for a package that did not include a referendum mechanism meant the final package was rejected by René Lévesque, and the myth of Quebec’s exclusion arose.

A day or so later, I sat with other constitutional law professors to settle on the materials for the coming school year when one of my colleagues mentioned in passing that we should add the Meech Lake Accord. I strongly objected, saying that it should never become law. To me, the Meech Lake Accord represented a complete reversal of the country’s constitutional evolution. It seemed obvious that it had the potential to create enormous rifts in, if not tear apart, the fabric of the Canada I loved.

In my view, Mulroney and the provincial premiers had made an enormous miscalculation in thinking that passing the constitutional resolutions through the legislatures with minimal debate was going to be easy. After patriation of the Constitution in 1982 and the introduction of the Charter, Canadians felt a sense of ownership in what was now seen as our constitution and would surely take offense at the idea that matters that would ultimately define Canada might be conducted behind closed doors. My instinct proved accurate almost immediately, as Canadians began to voice their distaste for such hasty reforms.

Even back then, I realized that our parliamentary system, dominated by established political parties, was not the way to fight Meech. Individual MPs and provincial legislators were expected to toe the party line once the leader made a decision, leaving no room for independence. This is true to this day, as I’ll demonstrate in future chapters.

To effectively mobilize citizens to oppose the Accord required organizing outside the established political parties. That’s why I abandoned the idea of trying for a nomination to be the Liberal Party of Canada candidate in the Beaches riding during the 1988 election campaign, and instead turned to organizing popular opposition. The Liberal leader, John Turner, strongly supported Meech from the beginning, and although a few Liberal MPs and candidates were critical of the Accord, they had no chance of exerting any influence in a House of Commons with a strong conservative majority. The best approach, I decided, was to spend my time organizing citizens outside the party structure, in hopes of convincing those who supported the Accord that they were wrong.

Recognizing that Mulroney was hell-bent on ramming the accord through the relevant parliamentary committees as quickly as possible, I spent the summer in my small office on the top floor of Falconer Hall, one of the two old U of T Law School buildings, contacting people across the country to build the foundations of a national organization. In those pre-Internet days, doing so required a lot of energy: phone calls, writing submissions for various people who wanted to appear before federal and provincial committees, and late-night photocopying sessions with volunteers preparing material that had to be sent via courier the next morning.

It astounds me to think what we could have accomplished then if we’d had access to today’s instant communications and social media networks. I believe opposition to the accord would have coalesced so quickly that it would have forced the first ministers to back down and spare Canada three terrible years of divisive and damaging debate that increasingly alienated citizens from self-absorbed political elites.

We organized from the grass roots, using little more than landline telephones and word of mouth, without the convenience of texting, email and social media. Individuals were encouraged to get any civil society group—or any other private or public association they were involved with—to oppose the accord. This expanded our civil society base to include women’s groups, indigenous groups, municipal councils, schools, the March of Dimes… the list was endless. What mattered was to build a consensus and develop a list of key concerns that all opponents could sign onto, so as to ensure our opposition was united and coherent, nationally based and not anti-Quebec.

Public debate intensified, spurred on by purposeful, intricate popular organizing. Protest happened through every possible outlet, inside and outside the provincial and federal legislatures. Proponents of the Accord labelled us “dissidents”, claiming we were “anti-Quebec” and out to weaken Canada—very much a prelude to the fearmongering and deliberate polarization of political messaging practiced so assiduously by the established political parties today.

The proposed constitutional amendments were controversial because they seriously undermined the role of the federal government and eroded the Charter of Rights and Freedoms’ vision of equal citizenship and a Canada-wide civic identity. For most Canadians, the decentralizing concessions demanded by the Quebec government (supported, unsurprisingly, by all the other premiers) were too high a price to pay for a largely symbolic vote of approval for the 1982 Constitution in the Quebec National Assembly. Despite Lévesque’s regrettable refusal to sign the final document, the 1982 Constitution had become the fundamental law of the land everywhere in Canada.

The political leaders of all the major political parties closed ranks to support the executive agreement reached by the heads of federal and provincial governments, without any consultation or engagement with citizens. Legislative committees were established in all the jurisdictions to examine the Accord, but most signatory governments had little trouble obtaining majorities to pass the necessary ratification resolutions through their respective legislatures––undeterred by growing public concern.

The Quebec government led the way by approving the Accord on June 23, 1987, and triggering the three-year time frame set out in the Constitution for obtaining all requisite ratifications (in this case, from all provincial legislatures, the House of Commons and the Senate). In so doing, they were following the amending formula introduced as part of the Constitution Act, 1982 that only requires approval of federal and provincial legislatures, and excludes the possibility of directly consulting citizens.

It was an exciting time of citizen mobilization. The multi-partisan coalition of opponents that I helped build endured through the three-year life of the Meech Lake Accord and beyond, to the Charlottetown referendum vote in October 1992. Our goal was always to criticize constructively and, wherever possible, present alternatives such as recognizing Quebec’s distinctiveness in the constitutional preamble so that the Charter would not be undermined.

We wanted to unite Canadians from all walks of life around common principles of equality, freedom and democratic participation. By connecting diverse citizen initiatives under a national roof, we cultivated a vibrant civic space for debate and action to address urgent collective concerns. This architecture—maintained through careful and tireless communication and organization—facilitated a proliferation of meetings and events across the country. (All my papers and records related to this period are deposited with Library and Archives Canada).

In Parliament, the Senate stalled its ratification process and held lengthy committee hearings that provided an invaluable outlet for the growing opposition. The Senate’s eventual rejection of the Accord was overridden by the House of Commons. Over the course of the ensuing three years, three new provincial premiers were elected who did not accept the Accord as it stood. New Brunswick ultimately passed a futile companion accord to address some criticisms.

In 1989, Newfoundland and Labrador elected a new premier, Clyde Wells. He had vocally articulated his principled opposition to the Accord, which had been approved by the House of Assembly under his predecessor. Premier Wells indicated that he was prepared to rescind the NL House of Assembly’s prior approval.

With very little hesitation, I accepted an offer to work with the premier as his constitutional advisor. Within two weeks I had moved from Toronto to St. John’s. Finally, an opportunity had emerged to realize the goals of our national movement to stop the Accord, provided the NL House of Assembly revoked its approval.

* * *

Premier Wells confronted Mulroney face-to-face at a First Ministers’ Conference in November 1989. The debate was broadcast live on television and replayed many times on newscasts. Unsurprisingly, Wells came across as a hero. Look no further than the polls for evidence. A majority of Canadians outside Quebec favoured the accord in 1987; by 1990, as Wells’ personal popularity soared, a majority opposed it. In particular, many Canadians became uncomfortable about giving Quebec “distinct society” status, which sounded like one province would be elevated above all the others. Wells had emerged as a national voice representing the opponents of Meech.

The basic details of Meech are well-known. Today, the debate may seem to some like a lot of wrangling over dry and convoluted constitutional minutiae; at the time, though, Meech was a wild rollercoaster ride for the entire nation.

Mulroney refused to back down, wrongly assuming Canadians could be persuaded to see the Meech Lake Accord in a positive light. Convinced that a deal with the holdout provincial premiers was all that was required, Mulroney initiated what turned into a marathon 70-hour negotiating session in a boardroom in Ottawa’s Conference Centre, at the very last moment before the June 23 deadline for approval. On June 9, 1990, Mulroney announced that a tentative agreement had been reached. The lone holdout was Clyde Wells, who agreed to present the compromise to his province’s legislature. A few days later, Mulroney gave an interview to The Globe and Mail. The story published on Tuesday, June 12 made it clear that the Prime Minister had deliberately timed the first ministers’ conference to ensure a crisis atmosphere, maximize pressure on the hold-out provinces, and leave so little time that Newfoundland would be unable to hold a referendum.

Though Mulroney’s revelation hardly surprised those familiar with his take-no-prisoners partisanship, his bluntness on this occasion was extraordinary. He described gathering his advisors at 24 Sussex a month before the June conference to map out a federal strategy. “Right here, I told them when it would be,” Mulroney said. “I told them a month ago when we were going to [meet]. It’s like an election campaign. You count backward. [I said,] ‘that’s the day we’re going to roll the dice.'”

At this point, all but two provincial legislatures had approved the accord, so the success or failure of Meech rested on Manitoba and Newfoundland and Labrador’s responses to Mulroney’s compromise. Manitoba premier Gary Filmon was in favour but faced a procedural hurdle. If he could not get all members of the Manitoba legislature to unanimously approve the compromise, public hearings would have to be held—a process that would stretch beyond the ten-day deadline. On June 12, the province’s lone Indigenous representative, Elijah Harper, strongly backed by Indigenous groups across Canada, refused to give his consent.

The resolve of the Indigenous leaders was inspiring and appropriate. Few were better placed to lead the opposition than the first peoples of Canada who, as so many pointed out, were more important, distinctive, and fundamental than any other group. They collectively dispelled naive notions that they could be bought off with minimal concessions thrown together by Mulroney and the pro-Meech forces. I can’t think of a better illustration of the vital need for any constitutional reform in this country to be transparent and open at every stage, taking into account the interests of all Canadians.

For the remaining days of the debate, I coordinated responses to over 12,000 letters, calls, and faxes received from across Canada during the ten-day period. Without exaggeration, 95 percent supported Wells—a tangible demonstration of how out-of-touch the other first ministers were with Canadians’ feelings about Meech.

At the Newfoundland and Labrador House of Assembly, the cabinet debated whether to hold a referendum or a free vote. A referendum proved impossible under the tight time constraint, so a debate was set to begin on June 20, giving the members of the House of Assembly time to return to consult their constituents in their respective districts. In the end, with backing from his caucus, Wells tabled a motion to adjourn, and the House voted in favour. A vote on the Meech Lake accord was thus deferred for good. But there was no doubt by those knowledgeable about the dynamics in the House of Assembly and the province, the vote would have been negative. Meanwhile, the people finally prevailed with one final wave of Elijah Harper’s feather, as he thwarted the unanimous vote in the Manitoba legislature.

In the midst of all the political manipulation, some in the media became extraordinarily engaged in actively supporting Meech. Those of us organizing in opposition to the Accord had to learn to grow a thick skin, stand by our principles and not be provoked by unfounded attacks and other efforts to stigmatize us. This was never easy. A few days before the Accord expired, then leading Globe and Mail commentator Jeffrey Simpson penned a direct personal attack on me and my counterpart in Manitoba, entitled “Wherever the Meech flame flickers, there they’ll be with a snuffer”, and arguing that if we were wrong about the need to defeat the Accord, “Canada as we know it is finished.”

A year later, the Montreal Gazette‘s brilliant cartoonist, Aislin (Terry Mosher), captured everything that was wrong with Meech in one simple image. It depicts Wells asking Mulroney, “But if Meech was as important to Canada as you’ve always said it was, why didn’t you let Canadians vote on the matter?” Mulroney replies: “Because, Clyde, it was far too important.”

When Meech died, all of us who had opposed the Accord hoped our experience would ensure that any future constitutional amendments would be grounded in open, principled debate and direct consultation with the people of Canada, to prevent such a debacle from ever recurring. We were to be disappointed. Despite key advisors’ advice to the contrary, Mulroney forged ahead with a new round of constitutional talks that would become known as the Charlottetown Accord.

***

The new initiative led by Joe Clark did involve public consultation, but this was carefully managed to sideline opposition, constrain popular engagement and ensure majority legislative support in all provinces and territories. The new package of even more extensive reforms was quickly dubbed “Meech plus”. This time, the Charlottetown Accord appeared to garner not only the support of all premiers, but of Indigenous leaders as well.

Fortunately, Mulroney opted to call a consultative national referendum, seeking what he hoped would be such unambiguous support for the constitutional amendments across Canada that expeditious ratifications by all legislatures would follow easily. The political elite, media, and both the cultural and business communities supported the Charlottetown Accord. Liberals either endorsed it or retreated to the sidelines. Even Clyde Wells was on board, judging that sufficient progress had been made toward Senate reform and addressing Indigenous concerns.

As if he’d learned nothing from the failure of Meech, Mulroney set a low tone by calling opponents of the accord “enemies of Canada”.

Rather than encourage informed, polite dialogue, Mulroney persisted with the ill-advised strategy he had practiced during the Meech period. He deliberately polarized the constitutional debates by demonizing his opposition, something we sadly see happening more and more today. He labeled his opponents “dissidents,” accusing us of being anti-Quebec and destroying Canada. Throughout the referendum period, he continually argued that the country and its economy would collapse because of our irresponsible actions.

Finding economists and historians to publicly counter Mulroney’s bogus claims became a daily chore for our ‘No’ Committee. When the Blue Jays won their first MLB World Series championship in the final few days of the referendum campaign, Mulroney rushed out to congratulate the team. He then declared it a great day for Canada, just as it would be when we all voted, as we should, in favour of the Charlottetown Accord. Our ‘No’ Committee immediately responded with congratulations to the Blue Jays, of course, specifying that the World Series results had nothing to do with our constitutional future, and that all Canadians would be building a stronger Canada by voting No to the Accord.

More personally, shortly before voting day, I came home to find a menacing death threat on my message machine warning me to stop opposing the Accord. The local police could do nothing to trace the call. They simply warned me to keep my doors locked and watch out for anything suspicious––small comfort for a single mother living alone with a small child.